- AwesomeHive Team

- 0 Comments

- 1410 Views

One of the keys to writing a successful web application is being able to make dozens of AJAX calls per page.

Asynchronous programming used to be a challenge even for seasoned professionals, leading to aptly named phenomena like Callback Hell.

This is a typical asynchronous programming challenge, and how you choose to deal with asynchronous calls will, in large part, make or break your app, and by extension potentially your entire startup. Asynchronous programming is a part of our everyday work, but the challenge is often taken lightly and not considered at the right time.

History of Asychronous JavaScript

The first and the most straightforward solution came in the form of nested functions as callbacks. This solution led to something called callback hell, and too many applications still feel the burn of it.

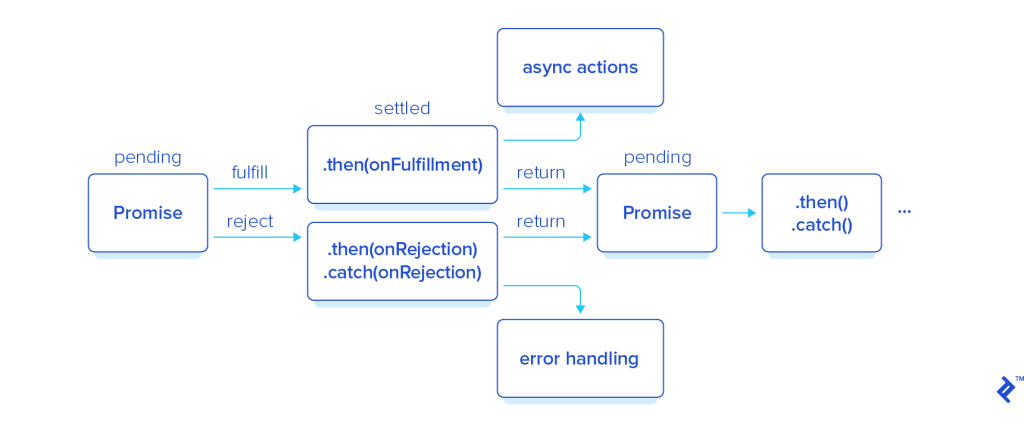

Then, we got Promises. This pattern made the code a lot easier to read, but it was a far cry from the Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY) principle. There were still too many cases where you had to repeat the same pieces of code to properly manage the application’s flow. The latest addition, in the form of async/await statements, finally made asynchronous code in JavaScript as easy to read and write as any other piece of code.

Let’s take a look at the examples of each of these solutions and reflect on the evolution of asynchronous programming in JavaScript.

To do this, we will examine a simple task that performs the following steps:

- Verify the username and password of a user.

- Get application roles for the user.

- Log application access time for the user.

Approach 1: Callback Hell (“The Pyramid of Doom”)

The ancient solution to synchronize these calls was via nested callbacks. This was a decent approach for simple asynchronous JavaScript tasks, but wouldn’t scale because of an issue called callback hell.

The code for the three simple tasks would look something like this:

const verifyUser = function(username, password, callback){

dataBase.verifyUser(username, password, (error, userInfo) => {

if (error) {

callback(error)

}else{

dataBase.getRoles(username, (error, roles) => {

if (error){

callback(error)

}else {

dataBase.logAccess(username, (error) => {

if (error){

callback(error);

}else{

callback(null, userInfo, roles);

}

})

}

})

}

})

};

Each function gets an argument which is another function that is called with a parameter that is the response of the previous action.

Too many people will experience brain freeze just by reading the sentence above. Having an application with hundreds of similar code blocks will cause even more trouble to the person maintaining the code, even if they wrote it themselves.

This example gets even more complicated once you realize that a database.getRoles is another function that has nested callbacks.

const getRoles = function (username, callback){

database.connect((connection) => {

connection.query('get roles sql', (result) => {

callback(null, result);

})

});

};In addition to having code that is difficult to maintain, the DRY principle has absolutely no value in this case. Error handling, for example, is repeated in each function and the main callback is called from each nested function.

More complex asynchronous JavaScript operations, such as looping through asynchronous calls, is an even bigger challenge. In fact, there is no trivial way of doing this with callbacks. This is why JavaScript Promise libraries like Bluebird and Q got so much traction. They provide a way to perform common operations on asynchronous requests that the language itself doesn’t already provide.

That’s where native JavaScript Promises come in.

JavaScript Promises

Promises were the next logical step in escaping callback hell. This method did not remove the use of callbacks, but it made the chaining of functions straightforward and simplified the code, making it much easier to read.

With Promises in place, the code in our asynchronous JavaScript example would look something like this:

const verifyUser = function(username, password) {

database.verifyUser(username, password)

.then(userInfo => dataBase.getRoles(userInfo))

.then(rolesInfo => dataBase.logAccess(rolesInfo))

.then(finalResult => {

//do whatever the 'callback' would do

})

.catch((err) => {

//do whatever the error handler needs

});

};To achieve this kind of simplicity, all of the functions used in the example would have to be Promisified. Let’s take a look at how the getRoles method would be updated to return a Promise:

const getRoles = function (username){

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

database.connect((connection) => {

connection.query('get roles sql', (result) => {

resolve(result);

})

});

});

};We have modified the method to return a Promise, with two callbacks, and the Promise itself performs actions from the method. Now, resolve and reject callbacks will be mapped to Promise.then and Promise.catch methods respectively.

You may notice that the getRoles method is still internally prone to the pyramid of doom phenomenon. This is due to the way database methods are created as they do not return Promise. If our database access methods also returned Promise the getRoles method would look like the following:

const getRoles = new function (userInfo) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

database.connect()

.then((connection) => connection.query('get roles sql'))

.then((result) => resolve(result))

.catch(reject)

});

};Approach 3: Async/Await

The pyramid of doom was significantly mitigated with the introduction of Promises. However, we still had to rely on callbacks that are passed on to .then and .catch methods of a Promise.

Promises paved the way to one of the coolest improvements in JavaScript. ECMAScript 2017 brought in syntactic sugar on top of Promises in JavaScript in the form of async and await statements.

They allow us to write Promise-based code as if it were synchronous, but without blocking the main thread, as this code sample demostrates:

const verifyUser = async function(username, password){

try {

const userInfo = await dataBase.verifyUser(username, password);

const rolesInfo = await dataBase.getRoles(userInfo);

const logStatus = await dataBase.logAccess(userInfo);

return userInfo;

}catch (e){

//handle errors as needed

}

};Awaiting Promise to resolve is allowed only within async functions which means that verifyUser had to be defined using async function.

However, once this small change is made you can await any Promise without additional changes in other methods.

Async – A Long Awaited Resolution of a Promise

Async functions are the next logical step in the evolution of asynchronous programming in JavaScript. They will make your code much cleaner and easier to maintain. Declaring a function as async will ensure that it always returns a Promise so you don’t have to worry about that anymore.

Why should you start using the JavaScript async function today?

- The resulting code is much cleaner.

- Error handling is much simpler and it relies on

try/catchjust like in any other synchronous code. - Debugging is much simpler. Setting a breakpoint inside a

.thenblock will not move to the next.thenbecause it only steps through synchronous code. But, you can step throughawaitcalls as if they were synchronous calls.